Stefan Herda and Tyler Muzzin will be exhibiting at Tess Marten’s The Front Room Gallery this month. The opening night is Friday March 29th from 7:30-9:30 pm. Tess interviewed both artists ahead of the exhibition. Follow @thefrontroomgallery on Instagram.

Martens: How do you two know each other?

Herda: Truth be told, Tyler and I know each other rather obliquely, and through mutual friends from the University of Guelph such as yourself, Sam de Lange, Nadine Maher, Kate Szabo and Nick Silvani and the rest of that gang. I graduated from the Studio Art program back in 2010, and if I am not mistaken Tyler finished his time a few years later.

Muzzin: I think we first met at Brass Taps (University of Guelph campus pub) right before Michael Snow’s Shenkman Lecture, though I knew of Stefan and his work prior to that through mutual artist friends.

Martens: Tell me about what you are doing now.

Herda: I am focusing on studio work at home, crystallizing various things and reviving old ink projects. My studio work is in transition right now, as we approach spring I have a plan to shoot several time-lapse videos and durational videos in nature that I having been mulling over, so I might be taking a page from Tyler’s book.

Muzzin: I’m currently working toward my MFA thesis exhibition at the University of Lethbridge where I plan to graduate this summer.

University of Lethbridge

Martens: How do you find your work connects to each other?

Herda: There are many parallels, but I think the most significant for me is the mutual interest in exploring nature, the passage of time, obsolescence and exploring the overlooked implications of our many human interventions on the natural world. We both encourage natural forces as collaborators or influencers on our work, through documenting decay and weathering. There are many parallels, we have been talking about showing together with other like-minded friends for some time now.

Stefan Herda, Organic Form. Aluminum Potassium Sulfate on Somerset Black Velvet paper. 30" x 22". 2012.

Muzzin: I sense a mutual curiosity about physical environments and a close eye to natural processes; with Stefan’s geodes, it’s the process of crystal formation and with the clapshacks it’s the process of entropy on built structures. There is also an openness to media experimentation and a diversity of methodological approaches. I’m always excited and surprised to see what he’s cooking up.

Tyler Muzzin

YOU MUST CHANGE YOUR LIFE (2018)

lumber, paint, vinyl

inkjet print mounted on Plak-It, 22" x 30"

Martens: How do the environment and civilization come up in your practice?

Herda: For the Clapshack work, the fading, eroding subject matter is a pretty clear Romantic trope exploring how nature inevitably reclaims civilization, this historic idea of the sublime. The paintings also explore a sense of nostalgia for the country (I was a suburban kid) through portraits of forgotten architecture, almost watercolour versions of the Becher’s photo typologies. The interplay between natural forces of change reclaiming or mutating civilization is a thread binding many of my projects and has been since my initial exploration into the chemistry behind the materials many artists use. Making my own fugitive, natural inks has always served as an experiment between civilization and environment, exploring domestic technologies and natural materials that has evolved gradually into much of the work I do with cultivating home-made crystals today.

Stefan Herda, Detroit Clapshack. Homemade Inks and Dyes on Arches paper. 30" x 22". 2010.

Muzzin: Much of my recent stuff questions whether or not those things can ever be exclusive. Humanity is as much a product of environment as it is an influence on it. Once we entered the Atomic Age and what many are now calling the Anthropocene, the gap between environment and civilization became nullified – even though the Cartesian model of Nature versus Culture continues to persist in the public imagination.

Tyler Muzzin

Private Property (2017)

vinyl on dibond

10" x 14", 8 variations, edition of 4 each

Martens: Risk is what I think about with both your work; risk of the structures collapsing and health risks with the ticks. Can you talk about that risk that should be immediately brought to attention? And how do you take risks in your art?

Herda: I think the main risk taken is not just from the subject matter depicted as being fragile, ready for collapse, but also materially from a conservation standpoint. I am working with unstable, fugitive inks that are both sensitive to light and the air. So much like the subject matter themselves, the paintings have the potential to fade, erode and change over time. I kind of stick my tongue out at this recurring concern to preserve or maintain painting, or that a painting is somehow precious because it maintains this idea of permanence, (which is impossible) and from a collector’s, dealer’s or “art market” perspective this technical decision could be seen as a commercial death sentence.

Stefan Herda, Highway Ten Clapshack #2. Homemade Inks and Dyes on Arches paper. 30" x 22". 2012.

Muzzin: The proliferation of ticks, especially those carrying the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, which causes Lyme Disease, is relatively recent in many parts of Canada. When I was growing up in Southern Ontario, there were rumours of deer ticks down around the southern-most areas of Point Pelee and Pelee Island, but they seemed less of a health risk and more of a creepy little neighbour that would leave you alone if you stayed out of the tall grass. A few decades later, ticks have entered public discourse and people are learning about the symptoms and dangers of Lyme Disease. The Stuffed Ticks operate as propositional tools that are both educational and absurd. With regard to my own practice, I’m not much of a risk-taker - but I did adopt a wood tick for a couple weeks and it was slightly unnerving to have it in a jar beside my bed. I named it Terry.

Tyler Muzzin

Stuffed Ticks (2018)

scraps of fabric, stuffing

Martens: To me, both your work is ugly/beautiful. Would you say your work ugly/beautiful?

Herda: Yes, totally. I draw a lot of influence from wabi-sabi, the Japanese aesthetic that finds the beauty in imperfection, accepting the patina of time and decay and encouraging a level of roughness and the handmade.

Stefan Herda, Highway Ten Clapshack #3. Homemade Inks and Dyes on Saunders paper. 30" x 22". 2013.

Muzzin: Some have described the Ticks as attaining a delicate balance between cute and disgusting. I think it’s because of their uncanny nature as objects that signify both comfort and strangeness, so it was important when choosing the fabric and scale to make them neither too cuddly, nor too repulsive.

Martens: Both of you use traditional ways of making. Stefan, you use watercolour and Tyler, you use fabric and thread. Tell me about the significance of your material choices.

Herda: I feel the material choices are so significant for this project, that these paintings would seem pedestrian and boring if it weren’t for the materials used. Working with homemade inks and natural colours, embracing the risk of having the paintings erode and encouraging their change is the main intention. The material choices are not just there for that ethereal aesthetic or a formal choice alone, but by their ephemeral nature, they connect to the broken down buildings crucially through that mutual erosion over time.

Stefan Herda, Nebula #6. Homemade Inks and Dyes, Tap Water, Rainwater, Vinegar, Bleach, Salt on Arches Paper. 30" x 22". 2011.

Muzzin: I selected an assortment of fabrics from a textile warehouse scrap bin. I didn’t want the ticks to look like mass produced merchandise. It was important that they resonated with a homemade DIY aesthetic. Once I had established the pattern, their construction was to be universalized to the point that anyone could make one. In this way, their creation can mimic the broad dispersion that ticks are currently enjoying with warming climates. I’d also like to send a shout-out to artist Grace Wirzba who did an impeccable sewing job.

Grace Wirzba

Martens: How do you decide on your colours?

Herda: Because I am incorporating colours sources from nature and my immediate surroundings, I am limited to a certain degree. For years, getting a hot pink or acidic green seemed impossible based on the limitations I imposed on myself. But through a bit of chemistry and research into traditional dyeing techniques, it is astounding what sort of colour range can be achieved through household chemistry.

For the blues I am using copper, copper wire mixed with vinegar creates copper acetate, essentially a patina paint. The purples are just pomegranate juice leftovers, concentrated with other salts. I decide what to extract and what to collect, and the process of refining and making them viable to use often leads to complete surprises and unexpected colour choices. There is an element of this left chance because between the extraction of the colour and the end results due to oxidation and other reactions, there can be a huge shift in what ends up on paper.

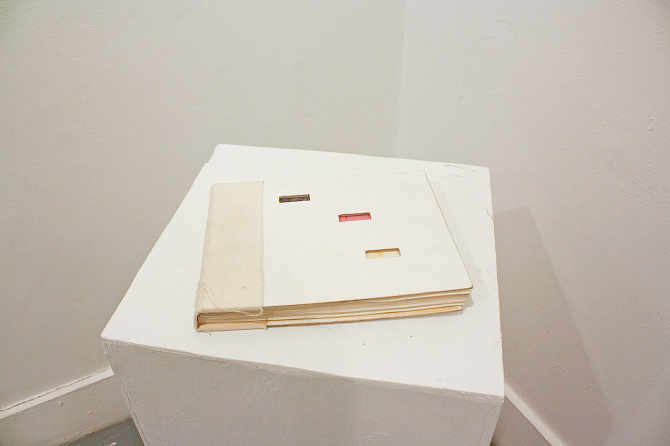

Stefan Herda, Colour Manual. Hand bound book, mixed media. 9" x 11.25". 2010. 45 pages.

Muzzin: The thing about ticks that disturbs me the most is their legs and the way they meander so casually, unlike other arachnids. For this reason, I wanted the legs to be the same colour and I chose a muddy, earthy grey. For their bodies, it was important to emphasize the teardrop shape that is often used to identify different species. I tried as best I could to combine the most clashing patterns, usually combining an ambient woodsy pattern with an artificial geometric or floral pattern. This way, they would escape associations with mass-production. The combinations reminded me of the blankets my grandmothers would make with a randomness that derived from a material frugality.

Material Scrap Pile

Martens: What should we look forward to for both of you moving forward?

Herda: Well, I was recently accepted into the Landscape Architecture Program at U of T, so much of my research will be shifting to Landscape Design and Urbanism with the intention for my degree to inform larger scale public projects exploring nature and ecology. I do plan on continuing to make more and more sculptural work and supplementing that with video projects in the meanwhile though.

Stefan Herda on Steve TV for Axe Throwing

Muzzin: Almost all of my work is in some way a response to the place where I’m living, so it will likely depend on where I end up post-MFA. An impending reality that is equally daunting and exciting for me.

Tyler Muzzin, Windbreak, 2019

Martens: Thanks so much!

If you liked this interview, please like, comment, and share

About Tess

You can spot Tess Martens performing with all her heart during karaoke night because she has to compensate for her singing voice or cracking jokes at a music open mic night. She is a performance artist and painter that exploits her vulnerabilities and humour. When she is not doing art, she is working with seniors. She recently received her Masters of Fine Art at the University of Waterloo. She now resides in Waterloo, Ontario. Follow Tess on Instagram.